The Dunning-Kruger Effect is generally defined as a cognitive bias in which individuals incorrectly OVERESTIMATE their abilities or knowledge in a specific area. A typical example is if we take a quiz about something specific and believe we did really well, yet grading shows the opposite.

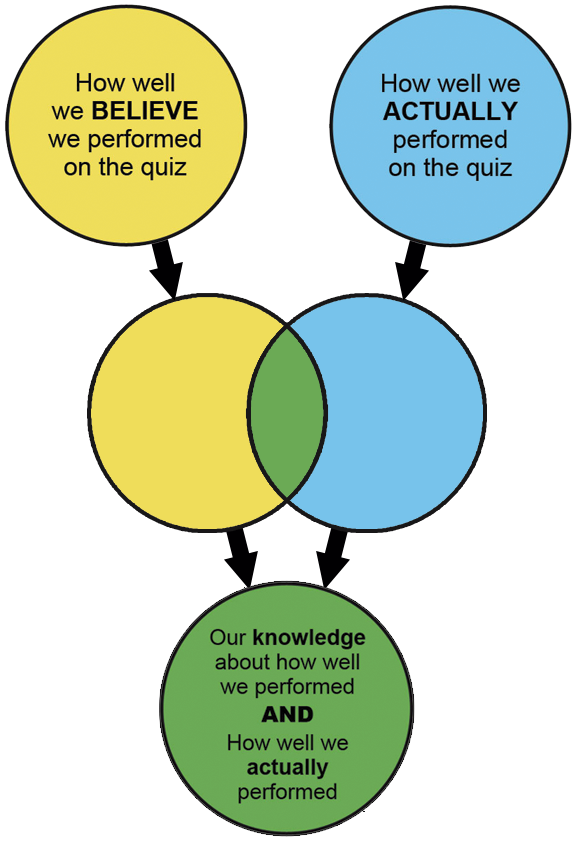

If we believe we aced a quiz, we believe the answers we gave were aligned with the objectively correct answers…that the circle of our knowledge perfectly overlapped with the circle of objectively true information. Our belief is shown to be in error when we get our grade; the circle of our belief about our performance didn’t overlap the reality of our performance at all!

The disconnect between how well we do and how well we believe we do is often chalked up to a lack of metacognition—a failure to recognize our own ignorance in specific areas. That our knowledge was wrong is not the issue here; that we believed it was right is far more concerning because holding that belief keeps us from realizing we have anything to learn/change/improve.

Most of us probably remember being given a test as children and told to read through the whole test before starting…and then finding out several embarrassing minutes later that there were instructions on the last page that instructed us to do nothing more than write our names on the test. Oops! It can be so easy to believe we have performed better than we truly did. Add in that there are things we aren’t even aware we don’t know (“unknown unknowns”) and we can begin to feel a sense of helplessness.

What should we do?

Knowing how well we performed at something, as opposed to simply holding a belief about our performance, requires more than doing the thing and consulting our intuition.

To correct for any cognitive bias and tendency to overestimate our performance, we must use a rational (knowledge-based) strategy similar to this one:

- Identifying and clarifying performance expectations

- Setting or being aware of performance criteria

- Determining the measures of success

- Measuring our performance against those standards

Applying these steps before and after doing something like taking a quiz will give us a much more realistic idea of how well we did. This is because the steps prompt us to engage in a rigorous and metacognitively-focused process of planning and analyzing our performance with respect to the objective requirements and criteria of the performance.

Through this process, we learn 1) how well we should expect to do, 2) what a successful performance looks like, and 3) how to measure our own performance, bringing the circle of our understanding about our performance into effective overlap with the circle of the reality of our performance. Voila!

Well, once again I find great joy in a blog. in my world I have often had to “grade” the performance(s) of people in a team environment, who have been asked to work collectively, usually for a five-day, forty-hour workshop. These workshops have covered various topics for capital projects during the planning stage or a project: including value engineering, risk analysis/mitigation, constructability and others. I have used phrases like “please leave your design engineering bias at the door” to try to get the right mindset(s) for a collaborative, collegial, and comprehensive report for a project sponsor or owner.

This blog has great applicability to commercial work as well as academic pursuits. Asking subject matter experts to think “outside” the box can be problematic. Some subject matter experts cannot divorce their bias about other viewpoints from the constraints imposed on them by conventional thinking, existing codes and practices, etc. An example is the use of analysis of a project’s elements by focusing on the function that a particular element is trying to achieve. “Increase the hydraulic gradient” is a function that is more generic than “pump water” and can open your eyes to other methods of achieving the goal of increasing the hydraulic gradient.

There are many uses for the intellectual properties that are part of process education that can be beneficial toward our own beliefs and how well we actually perform in our daily lives and our work.

Pingback: A Bit of FGB for ME! | Academy of Process Educators NEWS

Understanding the power of this capability is due to watching the performance of Marie Baehr for 30 years. She is the strongest I have seen with the capability of knowing exactly where she stands with the performance delivered against the expectations set. Her self-analysis of her performance is consistently very close to the level of performance delivered. She can often even tell you about the relationship between a person’s own expectations of that performance and her alignment to meeting their expectations. This gives her choice and power in both current and future contexts of what she wants to do.